Introduction

As companies increasingly invest in data analytics and utilize data to make more informed decisions, there is a growing demand for students with skills in this area (e.g., Keiper et al., 2024; Liu & Levin, 2018). Consequently, marketing analytics has become an essential class to equip students with these crucial skills. For many marketing students, who often choose their major based on a preference for topics other than mathematics and analytics, the prospect of taking a marketing analytics course can be intimidating (Killian, 2023). Such perception can deter students from enrolling in the class or diminish their motivation to perform well.

This intimidation factor becomes particularly relevant for instructors who are considering alternative pedagogical approaches, especially when traditional teaching methods have resulted in low student course satisfaction in the past. The Student-Empowered Flipped Classroom approach presented in this study offers a viable alternative for instructors seeking to enhance student engagement and satisfaction in challenging quantitative courses.

Developing a holistic analytics capability for effective marketing practice requires a combination of four key components: conceptual knowledge, technical skills, tool proficiency, and soft skills (Kurtzke & Setkute, 2021). The literature indicates a need for continued curriculum innovation and alignment with industry needs (Dar et al., 2021). There is also a call for more research on effective teaching methods and assessment strategies for marketing analytics education (Skiera & Jürgensmeier, 2024; Ye et al., 2024).

The flipped or inverted classroom has emerged as a novel and widely embraced instructional model in recent years (e.g., Missildine et al., 2013), presenting great potential in addressing the aforementioned challenges. Previous research also indicates that the effectiveness of the flipped classroom is not always consistent and can vary depending on the specific design and implementation of the approach (Rotellar & Cain, 2016). To capitalize on the benefits of the flipped classroom while addressing its challenges, this study introduces a novel approach: the Student-Empowered Flipped Classroom (SEFC). Drawing on Thomas and Velthouse’s (1990) four conditions of empowerment—choice, meaningfulness, competence, and impact—we designed a framework that empowers students within the flipped classroom setting. By providing students with greater autonomy and incorporating elements that foster engagement and efficacy, the student empowered flipped classroom seeks to increase the learning experiences and outcomes.

Literature Review

The Flipped Classroom Methodology

The flipped classroom methodology has emerged as a transformative teaching approach that redefines traditional instructional paradigms. Instead of using the traditional division of in-class and at-home activities, the flipped classroom transforms content delivery into independent study outside the classroom and engages students in interactive learning experiences during class time (Bergmann & Sams, 2012). Its primary rationale is to enhance student engagement with content, improve the quality of faculty-student interactions, and ultimately enrich the overall learning experience (Rotellar & Cain, 2016).

Extensive research has highlighted the benefits of the flipped classroom such as the improvement of student learning performance (e.g., Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018) and enhanced student satisfaction (Missildine et al., 2013). While the flipped classroom has gained recognition as an effective instructional model, previous research has highlighted certain limitations, mainly related to inadequate student preparation prior to class, such as inadequate self-regulated behaviors among some students (Sun et al., 2017) and difficulties in managing out-of-class learning content (Lai & Hwang, 2016).

In order to mitigate these disadvantages, many researchers have explored different ways to design the flipped classroom. For example, Kim et al. (2014) identified nine critical design principles that underpin effective flipped classrooms, emphasizing a learner-centric philosophy. Some of these principles include providing students with an opportunity to gain first exposure to content prior to class, offering incentives for students to prepare, and ensuring clear connections between in-class and out-of-class activities. Additionally, fostering a learning community and offering timely, adaptive feedback further enhance the effectiveness of the flipped classroom approach. Estes et al. (2014) proposed a 3-stage framework for flipped classrooms, including its implementation through pre-class, in-class, and post-class learning activities. Although previous research has explored various strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flipped classroom, limited focus has been placed on student empowerment and the creation of a specific, actionable framework to design empowering flipped classroom assignments.

Student Empowerment

Empowerment is a process through which individuals gain control over their lives, including developing skills and accessing resources (Zimmerman, 1995). Student empowerment has received increasing attention in education as educators and researchers seek to understand how students can take an active role in their own learning and development. One of the foundational aspects of student empowerment is recognizing students as active participants rather than passive recipients of education. Previous research highlights that students’ self-perceptions, including their sense of relatedness and autonomy, significantly influence their academic engagement and performance (Furrer & Skinner, 2003). By fostering a sense of ownership and autonomy, educators can create environments where students feel more connected to their learning, leading to improved academic outcomes and personal development.

Marketing educators have introduced innovative approaches to empower students. For example, they connect classroom education with career exploration and job-skill development (Raska & Weisenbach Keller, 2021), implement co-creation strategies in which students actively contribute to designing their learning experiences (Zarandi et al., 2022), and provide opportunities for students to create their own learning concepts and activities (Drapeau, 2021).

While previous research has explored various ways to increase student empowerment, little research has focused on developing a specific framework to help educators design assignments that effectively empower students in the learning experience. To fill this gap, we adopt the empowerment framework developed by Thomas and Velthouse (1990), which focuses on four components of empowerment. Using a marketing analytics class as an example, we demonstrate how this framework can be applied to develop assignments that help students feel more connected to and in control of their learning experience, ultimately enhancing their satisfaction and learning outcomes.

Cognitive Components of Empowerment

Thomas and Velthouse’s (1990) research have been a cornerstone in organizational behavior studies, identifying four key cognitive components that drive intrinsic task motivation: choice, meaningfulness, competence, and impact. These dimensions collectively form the foundation of psychological empowerment, influencing a wide range of work outcomes.

Choice, also referred to as self-determination, represents an individual’s sense of autonomy in initiating and regulating actions (Gagné et al., 1997). It reflects the freedom people perceive in deciding how to approach their work, including methods, pace, and effort. Greater autonomy fosters a stronger sense of ownership and responsibility for tasks.

Meaningfulness pertains to the perceived value of one’s work in alignment with personal beliefs, attitudes, and values. When employees see their tasks as meaningful and consistent with their ideals, they are more likely to feel intrinsically motivated and engaged in their roles. Thomas and Velthouse (1990) define meaningfulness as “the value of the task goal or purpose, judged in relation to the individual’s own ideals or standards. In other words, it involves the individual’s intrinsic caring about a given task” (p. 672). They propose that meaningfulness reflects the investment of psychological energy in work tasks. When individuals find a task more meaningful, they tend to dedicate greater psychological energy to it.

Competence, also known as self-efficacy, is the belief in one’s ability to successfully perform job-related activities (Meng & Sun, 2019). Confidence in meeting job demands and excelling in their roles is crucial for people to feel empowered to make decisions and take initiative. Developing competence can significantly enhance people’s effectiveness and motivation.

Impact refers to the extent to which an individual believes they can influence strategic, administrative, or operational outcomes in the workplace. It reflects the perception of making a meaningful difference through one’s actions. When employees feel their contributions drive desired outcomes, they are more likely to experience empowerment and satisfaction. Thomas and Velthouse (1990) describe impact as “the degree to which behavior is seen as ‘making a difference’ in terms of accomplishing the purpose of the task, that is, producing intended effects in one’s task environment” (p. 672). Those who perceive their jobs or work roles as impactful are more likely to take on greater responsibility and experience stronger psychological empowerment than those who view their roles as insignificant.

Thomas and Velthouse’s empowerment model has been widely adopted in organizational research and has shown significant impacts on numerous positive work outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, work engagement, job performance, and innovative behavior (e.g., Zimmerman, 2000). This framework can also be applied to educational settings where student empowerment involves equipping students with the authority and agency to make decisions and implement changes within their educational environment.

Teaching Innovation: A SEFC Project

Overview of the Marketing Analytics Course

In the Marketing Analytics class, the instructor structures the course into three distinct parts over the semester, with each part comprising approximately ten classes, each lasting 75 minutes. The first part focuses on descriptive analytics and covers foundational topics such as the basics of marketing analytics and data visualization. The second part emphasizes predictive analytics, exploring concepts like data collection and regression analysis. The third part addresses emerging topics within the field, allowing students to investigate cutting-edge areas such as automated machine learning, natural language processing, and social network analysis.

The instructor begins with a traditional instructional approach during the first two parts to establish a strong foundation in marketing analytics and provide students with the essential knowledge needed for the course. The final parts adopts a flipped classroom approach, allowing students to explore emerging topics by selecting one of three subjects for their group project: automated machine learning, natural language processing, or social network analysis.

Overview of the SEFC Project

The instructor dedicated one class to discussing three emerging topics to help students understand the basics of these topics and their applications, particularly in the marketing field. The discussion included potential future careers related to these topics and ways to ensure students grasp their significance. Afterward, students were given a few days to decide which topic they would like to explore further. They then used a sign-up link to select their preferred topic. Students did not choose their groupmates; instead, they selected a topic of interest. Groups were automatically formed based on the chosen topics. Since there were three topics available, group assignments operated on a first-come, first-served basis. Once a group for a specific topic was full, students had to select their second choice. Eventually, each group was formed with a set number of members, and most students were able to work on their first-choice topic.

Each group functions as a study group, utilizing provided study materials specific to their chosen topic. The instructor meets with each group to review the main concepts and address any questions they may have while studying the materials. Furthermore, each group is tasked with understanding the concepts and completing a unique group project using different software relevant to their topic. For example, the automated machine learning group will utilize DataRobot, the natural language processing group will employ Python for sentiment analysis and topic modeling, and the social network analysis group will use Polinode to analyze tweet data.

Subsequently, each group delivers a 45 to 60 minutes presentation to teach the rest of the class about their chosen topic. These teaching groups not only convey the fundamental concepts but also showcase their group projects and demonstrate how the software can solve real-world business problems. Similar to regular instructors, the teaching groups need to engage their peers in the class through class activities and design quizzes to assess their understanding. The framework for organizing the course is shown in Figure 1.

Implementing Empowerment in a Flipped Classroom Project

Our project advances the flipped classroom model by integrating assignment components specifically designed to empower students through Thomas and Velthouse’s (1990) empowerment model. The ways in which each component of the assignment contributes to student empowerment are detailed below.

Choice. The assignment provides students with the option of selecting their group project topic from three options: automated machine learning, natural language processing, or social network analysis. This element of choice enables students to select a subject that corresponds with their interests and preferences, fostering a sense of autonomy and ownership over their educational journey.

Meaningfulness. The assignment also accentuates relevance by providing students with practical applications of the selected topics. By working on projects that utilize relevant software and techniques, students can directly apply their knowledge. This connection between theory and practice enhances the significance of the assignment and promotes a more thorough comprehension of the concepts. Another aspect that makes this experience truly meaningful for each student is the opportunity to choose a topic that aligns with their interests and future career goals. By exploring these topics and using relevant software for their projects, students understand that they are not just working to pass exams or earn credits for the class. More importantly, they are gaining valuable skills and knowledge essential for their future careers, making the learning process even more meaningful and relevant to them.

Competence. The assignment fosters competence by requiring students to study the provided materials and gain a thorough comprehension of their chosen topic. Students gain competence in the subject matter and confidence in their abilities to analyze and implement the acquired knowledge through group and individual efforts. The instructor also provides students with plenty of study materials and guidance on their specific topic. Each team will have a meeting with the instructor specifically for their group project. Before the private meeting, all the members are required to read all the study materials and the instructor will ask questions of the topic and provide feedback and correction if needed on students’ answers. Instructor will also give students plenty of time to ask questions. Many students believe this instructor-to-one group specifically meeting helps them tremendously while they are preparing to teach the topic and make them feel they can do it.

In addition to providing sufficient guidance on the teaching content, the instructor also gave clear instructions on how to organize their class. This included introducing the topic, leading in-class discussions, providing background on the case study, demonstrating the software, and showing how to use it to solve business problems. Each group was also tasked with designing a quiz to assess their classmates’ understanding. For many students who had never taught before, this structured approach offered clear guidance on both what to teach and how to teach it effectively. Such an approach helps students build confidence and equips them with the necessary competencies, allowing them to feel capable and reassured that the task is achievable.

Impact. The assignment also focuses on impact by giving students the opportunity to present their findings and projects to the rest of the class. The students take on the role of teachers for their assigned topic, sharing their insights, demonstrating the software’s applications, and engaging their classmates through class activities. These teaching groups enhance their peers’ learning experiences. This exchange of knowledge and the capacity to make an impact within the classroom community contribute to the enhancement of the overall learning outcomes. Demonstrating their ability to help classmates understand new concepts and teach them how to use the software highlights the impact of this assignment. This impact not only motivates students but also empowers them to learn the material thoroughly as they take on the responsibility of influencing their classmates’ learning outcomes through their teaching.

The main components of this flipped classroom group project that foster student empowerment is summarized in Figure 2.

Assessment

After each group completed their teaching session, the instructor provided feedback, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement in their presentation. Additionally, the instructor offered suggestions to enhance their presentation skills. Once all groups had finished presenting, an online survey with multiple-choice and open-ended questions was distributed to gather students’ feedback on the flipped classroom activities. This allowed students to share their thoughts on the experience and offer insights for further improvement. A total of 38 students completed the feedback questionnaire following the group teaching session where the majority of the students indicated that they found the group project is relevant and beneficial for their learning.

To ensure anonymity, the survey was designed to collect responses without capturing any identifying information, such as names or student IDs. Students submitted their feedback anonymously through the online platform, which did not link their responses to their identities. This approach allowed them to provide honest opinions without fear of their feedback affecting their grades or standing in the class. The questions use a 1-7 Likert scale to measure students’ attitudes, providing a structured way to assess their perceptions, understanding, and engagement with the class activities. Students’ satisfaction, the relevance of the group project, and the associated workload are also assessed. Learning and motivation for this project are measured using a scale adapted from Ngereja et al. (2020). In addition to evaluating their own projects, students also assess other groups’ performance to determine how effectively they led their teaching sessions.

Results and Discussion

The survey results provide valuable insights into students’ attitudes and perceptions regarding the SEFC project. Overall, the responses indicate a positive reception of the group project.

Satisfaction. Students expressed high levels of satisfaction with the group project, as evidenced by a mean score of 6.24 (SD = 0.786) for the statement “I am satisfied with this group project.”

Relevance and Workload. The study materials were perceived as relevant and meaningful, with a high mean score of 6.32 (SD = 0.702). Students also found the workload to be appropriate (mean = 6.26, SD = 0.685), indicating a well-balanced assignment structure.

Learning. The results indicate that the group project was effective in enhancing students’ learning and comprehension. Students rated the project highly in terms of encouraging them to rethink their understanding of the subject matter, with a mean score of 6.00 (SD=0.943). Additionally, the use of examples and illustrations in their presentations was rated high with a mean score of 6.11 (SD=0.953), indicating that these elements significantly contributed to their understanding.

Motivation. The results also show that several factors significantly motivated students to put in extra effort, including the project’s contribution to their final grade (mean = 6.47, SD = 0.725), its use as a learning aid (mean = 6.11, SD = 0.764), and the requirement to teach their peers (mean = 6.13, SD = 0.935). This highlights the importance of designing group projects with clear relevance and accountability mechanisms.

Collaboration and Team Dynamics. The majority of students enjoyed working with their team members, as reflected by a mean score of 6.05 (SD = 1.207).

The measurement scales and results are listed in Table 1.

Beside the assessment of student’s own project, we also assessed how students evaluate other groups’ performance to assess how effective other groups lead the teaching session. The results indicate that students generally found peer-led instruction to be effective and well-organized.

The overall effectiveness of student instruction received a mean score of 5.68 (SD= 1.093), suggesting that most students viewed the teaching positively, though some had differing opinions. Satisfaction with the efforts of student instructors was rated at 5.71 (SD=1.160). The highest-rated aspect was the preparation and organization of other groups, with a mean score of 5.87 and the lowest standard deviation (1.018), suggesting a strong and more consistent perception that groups were well-prepared. The minimum scores of 2 and 3 in these categories suggest that while the majority found the peer-led sessions effective, some students did not find them as impactful. Overall, the data highlights that student-led instruction was perceived as effective, with preparation and organization receiving the most consistent positive feedback.

Students Feedback from the Open-Ended Questions

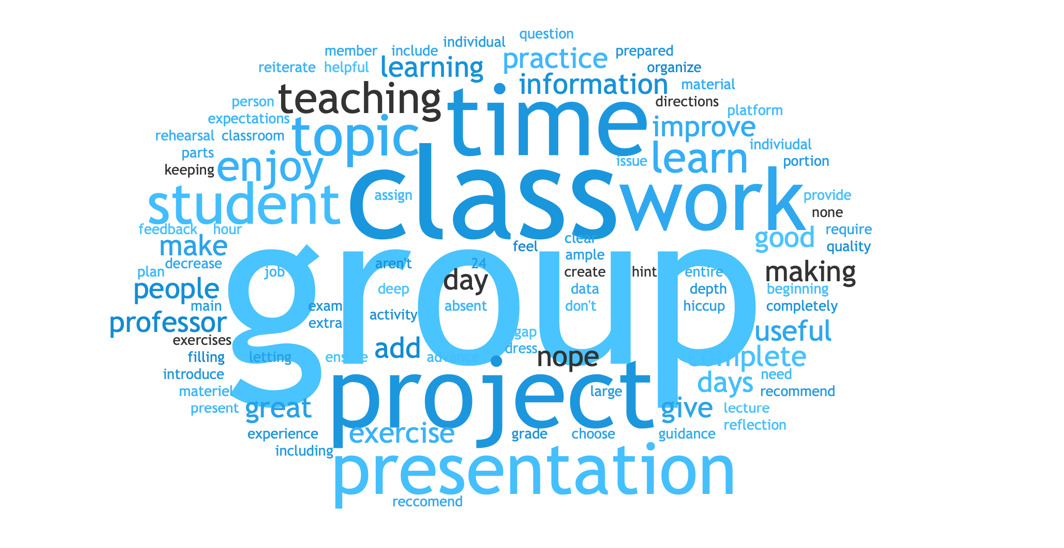

In addition to the multiple-choice questions, we also included three open-ended questions to allow students to provide more detailed and personalized feedback. The questions were: 1) “What did you like most about this group project?” 2) “What did you like least about this group project?” and 3) “Do you have any suggestions for improving the group project?”

The word clouds, based on the text analysis of students’ feedback on these three questions, are shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5.

We also analyzed the students’ responses to these questions using content analysis and summarized the key themes in Tables 2, 3 and 4. Representative comments were also included to illustrate the main findings that emerged from their feedback.

For the first question, “What did students like most about this group project?” many students mentioned that they appreciated using teaching as a learning tool. This demonstrates that the flipped classroom approach was highly effective, as teaching the topic helped students understand it better than simply listening to lectures or reading the study materials. Additionally, many students highlighted the value of collaboration and teamwork, noting that working in a group made learning more enjoyable and manageable.

Students also appreciated the engagement and creativity fostered by the project. They mentioned feeling empowered by being allowed to choose topics based on their interests, which made the learning experience more relevant and meaningful. Furthermore, many students commented on the support and resources provided by the professor, including guidance and study materials, which made complex concepts easier to understand. They also enjoyed the interactive teaching sessions with their classmates.

However, the main negative feedback about the group project was related to time constraints. Some students felt they had limited time to manage the project effectively. Others mentioned that the group size was sometimes too large, which made coordination challenging. There were also concerns about the difficulty of learning from other groups when those groups were not adequately prepared. Additionally, because groups were formed based on student interests rather than personal preferences, some students expressed a desire to work with their chosen classmates instead.

Suggestions for improving the group project included addressing these negative aspects. Students recommended allowing more time to prepare, reducing the overall size of the groups, and increasing instructor involvement. For example, they suggested the instructor review group projects one day before presentations to provide feedback and ensure that groups are well-prepared. Another suggestion was for the instructor to conduct a follow-up review session after all groups have presented to reinforce the key concepts and ensure all students achieve a similar level of understanding of the topics.

Overall, the feedback indicates that this flipped classroom approach was effective in promoting student satisfaction, engagement, and active learning. Students enjoyed the opportunity to use teaching as a learning tool. Moving forward, improvements could include providing more guidance to ensure the quality of student teaching, reviewing group projects in advance, and holding one or two review sessions at the end of the semester to reinforce students’ understanding of the material.

Theoretical and Practical Contributions

While previous research has explored various ways to increase student empowerment, little has been done to develop a specific framework that helps educators create assignments that empower students in their learning experiences. To address this gap, we adopt the empowerment framework developed by Thomas and Velthouse (1990), which focuses on four key components of empowerment. Using a Marketing Analytics class as an example, we demonstrate how this framework can be applied to develop assignments that help students feel more connected to and in control of their learning experiences, ultimately enhancing their satisfaction and learning outcomes. This study makes several theoretical and practical contributions for both researchers and educators.

First, this research makes a significant theoretical contribution by addressing a critical gap in the literature on student empowerment. While previous studies have examined various methods to enhance student empowerment, limited attention has been given to developing a specific, actionable framework that educators can use to design empowering assignments. By adopting the empowerment framework proposed by Thomas and Velthouse (1990), which emphasizes four key components of empowerment, this study extends its application to the field of education, providing a structured approach to fostering student engagement and autonomy.

Furthermore, by demonstrating the application of this framework in a Marketing Analytics class, the study offers concrete examples of how theoretical constructs can be translated into practical teaching strategies. This contribution not only advances our understanding of empowerment in educational settings but also bridges the gap between theory and practice, equipping educators with a clear, replicable model for creating learning experiences that enhance student satisfaction, engagement, and learning outcomes.

Lastly, from an educator’s perspective, this research provides a clear roadmap and guideline for teaching essential courses like Marketing Analytics, a critical yet often challenging subject for marketing students. It demonstrates how to effectively engage students in more quantitative areas by empowering them with choices, providing structured guidance throughout the learning process, and leveraging teaching as a learning tool. By allowing students to take on teaching roles, this approach fosters deeper understanding while enhancing their confidence and engagement in mastering complex concepts.

Limitations and Future Research

While this innovative student-empowered flipped classroom framework provides theoretical contributions and valuable practical guidelines, it also has certain limitations and presents opportunities for future research.

First, although this study found that students reported relatively high satisfaction and perceived the project as relevant and meaningful, their learning experience was not entirely consistent. Students generally felt that using teaching as a learning tool enhanced their understanding and engagement as it allowed them to take an active role in the learning process. However, some students noted that their learning experience depended on the quality of other groups’ teaching sessions. If a group did not deliver an effective session, it negatively impacted the learning experience of the other students. Future research should explore ways to design the project to ensure consistent learning outcomes regardless of each group’s performance. One potential solution is to introduce review sessions at the end of the semester to reinforce key concepts. Additionally, although the instructor currently meets with students to check their understanding, time constraints prevent a full review of their presentations in advance. Introducing a rehearsal or pre-evaluation phase may help enhance the effectiveness of each session.

Another limitation of the flipped classroom approach is that, while the instructor provides sufficient guidance on the group project, helps students understand the subject matter, and assists in organizing the class, most students have never had the opportunity to teach a topic before. As a result, some students feel they lack the necessary pedagogical skills to effectively communicate concepts, structure their lessons, and engage their peers. Teaching requires not only subject matter expertise but also the ability to explain concepts clearly, facilitate discussions, and manage classroom dynamics—skills that students may not have developed. To address this, instructors implementing the flipped classroom model could dedicate a specific class session or workshop to teaching students effective presentation and instructional strategies. This training could cover best practices in lesson planning, techniques for engaging an audience, strategies for fostering discussions, and methods for assessing student understanding. Additionally, instructors could introduce peer feedback mechanisms and rehearsal opportunities to allow students to refine their teaching approaches before their actual presentations.

Lastly, while the findings provide valuable insights into student empowerment and engagement in a marketing analytics class, it remains uncertain whether the framework would yield similar results in other marketing courses or across different academic disciplines. To enhance the generalizability of the framework, future research should explore its application in a broader range of courses, including both qualitative and quantitative subjects. Additionally, examining its effectiveness in disciplines outside of marketing, such as business, engineering, or the social sciences, could provide further evidence of its adaptability and impact. Comparative studies across multiple courses and institutions could offer deeper insights into how different student populations respond to the flipped classroom model and whether modifications are needed to optimize its effectiveness in various educational contexts.