Introduction

The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), the international accreditation standard for business schools, has emphasized experiential learning in its standards for higher education business schools (AACSB, 2023). Business schools have increasingly faced the dual challenge of integrating experiential learning frameworks into their academic programs while simultaneously fostering long-term positive societal impact (Berry & Workman, 2007; Brennan, 2014). In the absence of ownership or direct access to a real business, students complete their course projects based on case studies or simulations. Those projects are seldom revisited or utilized beyond the completion of the coursework. Externally, emerging threats such as COVID-19, alongside other persistent challenges, including the advancement of new technology, new competitors, a looming demographic cliff, and geopolitical uncertainties, have compelled businesses to adapt to an unprecedented environment that hindered in-person shopping. Universities face similar challenges in reacting to those changes. While some universities have launched branded merchandise to promote institutional identity and school spirit, most universities do not manage their products in conjunction with the pedagogical or entrepreneurial activities of their business schools. Instead, centralized university stores manage the logistics of merchandise production and distribution, e.g., Carnegie Mellon University (Carnegie Mellon University Athletics, n.d.), the University of South Carolina (University of South Carolina, 2014), Cornell University (Cornell University Store, n.d.), Quinnipiac University (Quinnipiac University Bookstore, n.d.), and the University of California Riverside (University of California - Riverside Bookstore, n.d.), or a third-party retailer such as Kansas State University (Kansas State University, n.d.). Alternatively, the University of Alabama developed its official tartan design in 2010 under the College of Human Environmental Sciences (The University of Alabama, n.d.). In 2015, the United Nations (UN) introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which emphasize the importance of generating societal impact across all sectors, including corporations and higher education (AACSB, 2015). Specifically, Goal 3 calls for efforts to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages” (United Nations, n.d.). Business schools have a critical role in bridging the gap between theoretical instruction and the cultivation of future leaders’ social responsibilities. The end goal of community engagement aligns with the UN’s objectives.

In the context of diverse approaches to creating experiential learning environments, Killian et al. (2023) highlighted the growing need for expanded experiential learning projects to refine students’ professional competencies. Specifically, students benefit by gaining hard and soft skills (Gruen et al., 2024) and learn how to operate online businesses (A. Kumar et al., 2015) in broader communities beyond the university campus.

This research presented a student-run business model designed to facilitate experiential learning and demonstrated measurable societal impact. The experience of managing a business while students are enrolled in college enhances students’ sense of belonging, connectedness with the university, and their professional competencies.

The Student-Run Business

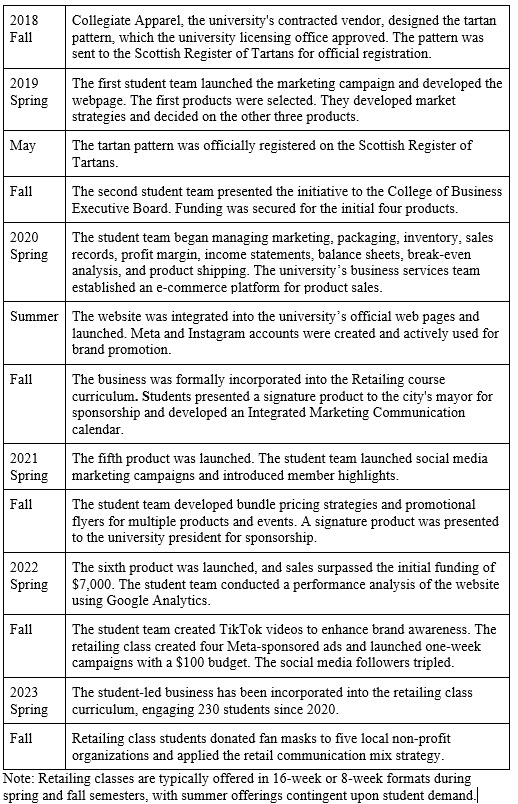

The tartan pattern registration process was initiated in early 2018, originating from discussions between College of Business faculty and students as part of a broader effort to create a student-run business. The concept focused on aligning with the university’s mission and strategic goals, ensuring both educational value and community engagement. Students and faculty prepared a comprehensive proposal, including budget estimates, product concepts, and anticipated societal impacts. Students presented this proposal to the College of Business Executive Committee in late 2018, where the project received approval and initial funding. The process of the funding request mirrored a professional fundraising pitch, in which students formally presented to the committee to demonstrate the need and long-term value of the business (see Table 1 for an overview of the funding process).

By early 2019, a multidisciplinary team of students, staff (administrative assistants and budget personnel), and faculty formed to manage operations, purchase the first inventory, and coordinate marketing strategies. The initial products arrived in Spring 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the challenges posed by the global crisis, businesses continuously revamped their business models to adapt to shifting consumer behaviors and navigate supply chain disruptions. Similarly, business schools responded proactively to reinvent course delivery to maintain students’ learning experiences and learning outcomes. Students were expected to experience campus life as part of experiential learning; however, this expectation became impossible during the pandemic. Although the pandemic disrupted traditional campus experiences, it also underscored the importance of flexible, real-world learning environments—reinforcing the value of experiential education even in times of uncertainty.

The student-run business played a pivotal role in compensating for the lack of interpersonal interaction during the COVID-19 pandemic, empowering students to think creatively and build brand awareness in a challenging environment. Following an initially turbulent phase, the funding and launch process established a replicable framework that can serve as a model for other higher education institutions seeking to develop student-run, mission-driven enterprises. The timeline of establishing the student-run, non-profit organization within the AACSB-accredited College of Business is demonstrated in Table 2.

Organizational Infrastructure

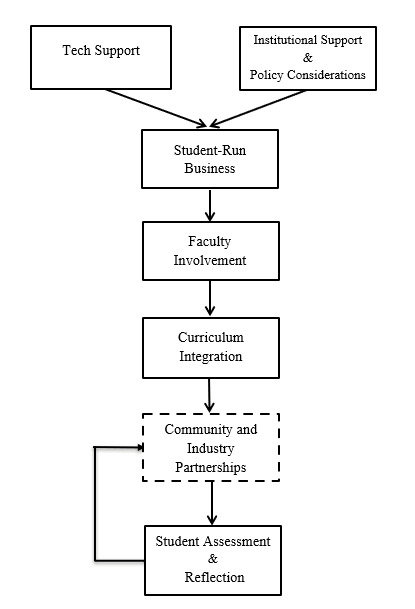

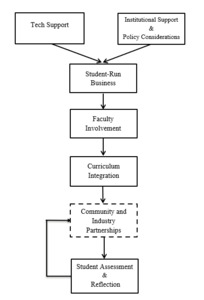

Under the university’s umbrella brand, the student-run business operates as a non-profit organization. Its structure incorporates the retailing class taught by the same instructor each semester and occasionally in summer. The student team (hereafter referred to as separate from students taking the retailing class) is constantly involved in the student-run business and understands the entire process and procedure. In contrast, the students in the retailing class were introduced to the business model for the first time each term. Within this framework (see Figure 1), the student team functioned like a corporate entity by managing business strategies to implement across stores. Students in the retailing class acted as store managers.

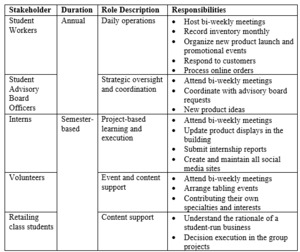

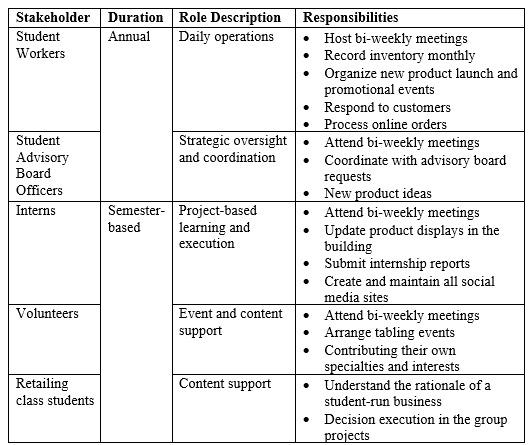

The student team operated independently from the retailing class and comprises interns, volunteers, Student Advisory Board members, and student workers. In contrast, students took the retailing class as an elective within their degree plan. The student team is responsible for securing approvals from the university’s Licensing, Marketing, and Communication Department and regularly presents to the Executive Advisory Board, alum groups, and fundraising audiences—opportunities rarely available outside the classroom. These experiences enhance their presentation and social skills while deepening their understanding of stakeholder engagement. The team also leads idea generation for websites, social media, events, and videos.

This structure enabled collaboration between the student team and retailing classes, enhancing students’ coordination and communication skills. The student team operated in a managerial role, offering guidance and insight while not directly overseeing task completion (evaluated by the instructor). This approach streamlined the development of promotional materials and marketing activities. For example, the student team handled setup logistics, while retailing class students created social media content aligned with a jointly followed integrated marketing communications calendar.

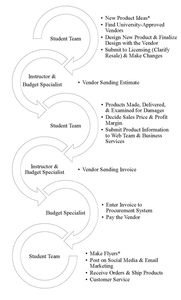

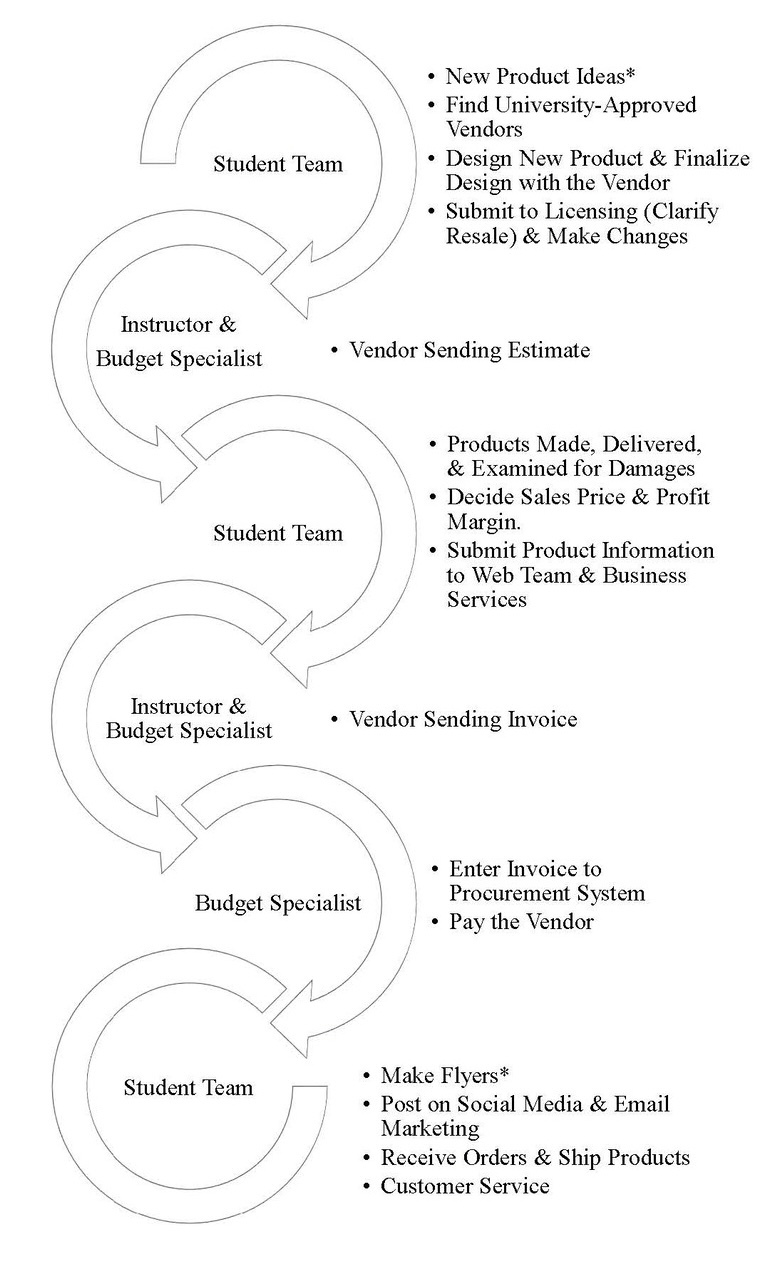

The student team focused on strategies to increase brand awareness and drive sales of their products. Each semester, the team typically consisted of three to ten students from both business and non-business majors. They were recruited through the Student Advisory Board, as well as interns, student organizations, volunteers, and student worker positions (see Table 3 for individual roles and responsibilities). The instructor of the retailing class oversaw the student team, allowing the business to operate autonomously. The instructor ensured vendor payments, with communications typically occurring among the College of Business budget specialist, the instructor, and vendors via email and phone (see Figure 2 for workflow).

The instructor also sought external funding within the university and recruited students from retailing classes each semester. When a new product was launched, the student team collaborated with vendors to present their product designs, and the finalized image was submitted to the licensing office for university approval. The student team determined pricing, designed marketing materials, and developed products, including t-shirts. They also communicated with vendors and distributed university-wide promotional emails. Students received three credit hours as a non-paid internship elective by participating in the student-run business.

As the student-run business operates continuously, ongoing efforts to maintain brand awareness are essential. The student team presented at new student orientations, classroom recruitments, city council meetings for community outreach, College of Business job fairs held annually, annual homecomings, and participated in giveaways and fundraising events through alum associations. The student team coordinated with the university’s chief communication officer to ensure alignment with promotional objectives.

eCommerce Marketplace

The university maintains an eCommerce hub serving all colleges. A third-party contractor processed all encrypted university transactions, including the sales from the student-run business. The Business Services office oversaw the platform, which supported secure payments and covered overhead costs for campus events, such as sports games, theatre performances, and summer camps. This department retained administrative access to the platform, whereas the student team did not. For example, the student team notified Business Services to update the available product inventory, and sizes upon receipt of new shipments or stock depletion. Profits from sales were deposited directly into a designated account, enabling the student-run business to reinvest in inventory, advertising, and operational expenses. The advisor and the budget specialist, within the College of Business, processed vendor purchases and payments (see Figure 2).

Website Design

Since the student-run business operated within the College of Business under the university’s umbrella brand, its design and layout were required to align with university standards for non-profit organizations. The university approved all website content, including product images, descriptions, and listings, prior to launch. This process fell outside the scope of the retailing class. In sum, the student team was responsible for organizing and launching the website content, while the retailing class remained separate from this responsibility.

We have provided an overview of the student-run business structure, including the roles of the student team and retailing class students. The organizational planning enabled meaningful community involvement. Based on this foundation, we formulated the research question: How did experiential learning impact students’ perceptions of community involvement? In the following section, we examined Kolb’s experiential learning theory as presented in the literature.

Literature Review

Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning theory (ELT) suggests that the learning process “whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combination of grasping and transforming experience” (p. 41). The model outlines four connected learning modes: concrete experience (CE), reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC), and active experimentation (AE). All four modes together form the foundation of effective experiential learning. Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning framework has been applied widely in marketing disciplines. Marketing educators integrated ELT into courses such as retailing (Cappuccitti et al., 2019; Rehncrona & Thufvesson, 2019), sales management and personal selling (Billups & Poddar, 2018; S. Inks et al., 2011; S. A. Inks & Avila, 2008; Rocco & Whalen, 2016; Serviere-Munoz, 2010), principles of marketing (Geringer et al., 2009; Myers, 2010; Schwartz & Fontenot, 2007; Wheeler, 2008; Young et al., 2008), digital marketing (Newaz & Nilson, 2024; Yang, 2019), and marketing research (Ayers & Underwood, 2007; Maher & Hughner, 2005).

Experiential learning (EL) assignments include simulations, client-based projects, fundraising initiatives, selling practices, and retail lab operations. Specifically, the applications include instructors tasked with developing meta-skills (Newaz & Nilson, 2024) and redesigning the university bookstore webpage as part of a user interface project (Yang, 2019) in digital marketing courses.

When EL projects involve non-profit organizations, they often incorporate service-learning components that engage community stakeholders. Service learning is a subset of ELT that emphasizes community engagement, as learning can be a social process (McGrath, 2023). Han and Stoel (2017) applied the Theory of Planned Behavior to understand socially responsible consumer motivations. These motivations illustrate the alignment between personal values and socially responsible behavior, reinforcing the importance of empathy and relevance in experiential learning projects. Kolb’s ELT provides a framework for extending students’ experiential learning experience, producing learning outcomes related to personal skill development and community involvement. Kumar et al. (2024) introduced the Transformative Marketing Education (TME) framework, which integrates AI, generative AI (GAI), and machine learning into curriculum design. Their emphasis on environmental responsiveness aligns with the student-run business model and its community engagement focus. Richter et al. (2024) propose collaborative projects with industry partners to produce marketing content, including social media audits and buyer personas, thereby bridging the gap between theory and practice. Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory (1985) outlines three stages of student learning: instrumental (how), dialogic (when and where), and self-reflective (why). These stages provide a valuable lens for evaluating student engagement in experiential projects, particularly those that involve real-world application of classroom knowledge. By fostering reflective practice and contextual understanding, student-run businesses can serve as platforms for transformative learning.

Benefits of Academic Community Engagement (BACE)

Miller et al. (2018) developed the Benefits of Academic Community Engagement (BACE) scale, which was based on the Service Learning Benefit (SELEB) scale, by testing the reliability and validity of four constructs: personal development, benefits to the community, social responsibility, and intended social responsibility in their study. The main purpose of the BACE scale was to assess students’ community engagement level, defined as “working to make a difference in communities through individual or collective actions designed to improve the quality of life” (Ehrlich, 2000, p. vi). When applied to projects involving nonprofit organizations, the BACE scale served as an effective measure of student involvement, particularly due to its emphasis on civic responsibility (Geringer et al., 2009; McGrath, 2023).

Role of the Instructor

The instructor taught the retailing class during the Fall and Spring semesters and occasionally in the summer. Serving as both facilitator and communicator, the instructor connected students enrolled in the retailing class with the student team responsible for making final decisions regarding the student-run business. Due to the registered and licensed nature of the business model, all products and promotional content required approval from the university’s licensing office. As the university operated as a public institution, the college’s budget specialist processed all expenses and vendor payments. The student team involved in managing the business did not have direct access to the monetary account designated for the student-run business. The instructor ensured that all communications and legal aspects of the e-commerce transactions were properly managed and handled.

Project Background

In 2020, the student-run business began selling fan masks as part of its product line. As the COVID-19 pandemic came under control, demand for masks declined, resulting in an accumulation of unsold inventory. To address this issue, a previous retailing class suggested donating masks to local organizations that can effectively utilize them.

During the summer online retailing class, the instructor adopted this suggestion and tasked students with researching local organizations. Their group project was to identify the events or client groups for which the masks would be used and estimate the number of masks each organization could accept. To ensure transparency, students sent photos of the masks and clarified that they were not medical-grade and were not intended for use in hospital or laboratory settings. After evaluating seven potential organizations, the student team selected five based on the quality of student reports. These five organizations responded promptly and provided clear descriptions of how the masks would be utilized. As a result, the organizations understood the nature of the masks and agreed to use them appropriately, without compromising the health or safety of their clients.

In alignment with AACSB Standard 4, which emphasizes fostering a “meaningful learner-to-learner and learner-to-faculty academic and professional engagement” as well as extending further to develop a course outline with “innovation, experiential learning, and a lifelong learning mindset” (AACSB, 2023). The distinctiveness of the student-run business model rendered the course innovative, providing students with direct experiential learning through problem-solving for an actual business. More importantly, the student team received an internal grant of $3,000. The team collectively agreed to use the grant to purchase fan masks intended for general sales.

Assignment Description

Students in the retailing class first learned about the student-run business (see Table 4) and five community organizations, each with its primary functions. As part of the assignment, they then applied the retail communication mix by promoting the event through owned or earned media channels, both before and after the event. The objective was to encourage students to initiate relationship-building efforts with the community.

Course Structure and Its Application Through the Experiential Learning Model

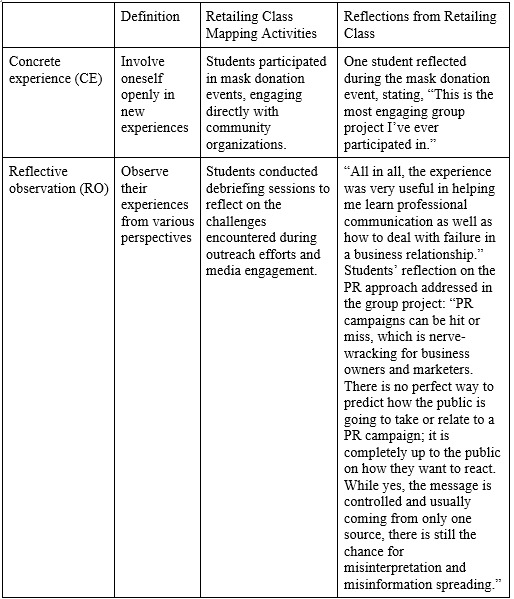

The retailing class first integrated the student-run business into its curriculum in Fall 2020 (see timeline in Table 2). This business served as a platform for experiential learning across disciplines. Moreover, the business model provided continuity by allowing students to work on the same enterprise across semesters, rather than initiating separate projects each term. The retailing class’s group project was designed for students to engage in all four stages of Kolb’s (1984) learning experiential theory. Table 5 presents each mode of experiential learning, including its definition, alignment with specific retailing class activities, and student reflections or quotes from the written report that illustrate their learning experiences.

The development of the student-run business took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period when face-to-face discussions and meetings were prohibited. This timing presented a unique opportunity, as the real-world businesses faced comparable challenges during and after the pandemic. The foundational value of the student-run business lies in its role as a practical outlet for retailing class students to apply theoretical knowledge in real-life contexts beyond the classroom.

Preparing for the group project, which was based on a real business, required substantial planning. Table 6 outlines the preparation process for pre-, during-, and post-assignment phases, corresponding with the timeline presented in Table 2. For example, obtaining approval from the university’s licensing office and establishing the business infrastructure were necessary steps prior to implementing the assignment. While institutional procedures may vary, the pre-, during-, and post-assignment checklists can serve as a helpful guide for instructors considering the integration of a student-run business into their curriculum. Importantly, the duration of the university’s approval process should be considered when planning such curricular initiatives.

Method

At the end of the 16-week course, retailing class students completed an anonymous two-page in-person survey using the BACE scale (Miller et al., 2018). The survey was designed to measure students’ attitudes toward the fan mask donation events delivered in five non-profit organizations. While the original BACE scale used a five-point Likert scale, this study adopted a six-point scale to eliminate a neutral midpoint. The even-numbered points had been discussed in the literature regarding their impact on response quality and scale sensitivity (Chyung et al., 2017). Indeed, research has shown that respondents may select the midpoint by default due to indecisiveness or lack of engagement (Simms et al., 2019) or use it as a “dumping ground” for items perceived as unfamiliar, ambiguous, or socially undesirable (Chyung et al., 2017). Such tendencies may compromise the validity of the construct being measured.

The instructor examined each survey immediately after students submitted their surveys in class, which eliminated the need for embedded attention check items. Two students initially completed only one side of the survey and were asked to finish the second page, ensuring no missing data.

The survey consisted of 19 items in total (see Appendix A). A total of 32 students completed the survey during the Fall 2023 semester, following the mask donation events. The sample included eight juniors, 23 seniors, and one sophomore. Students represented a range of academic majors, with the majority in marketing (n = 23), followed by general business (n = 3), management (n = 2), and one student each from computer information systems, agribusiness, animal science, and communication studies. The gender distribution included 15 male and 17 female respondents, with an average age of 21 years.

The retailing class, an elective course within the Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) program, represented a small sample of upper-level business students. Several non-business students enrolled in the course were pursuing a minor in business. Students enrolled in the retailing class were required to complete Principles of Marketing as a prerequisite.

Results

The BACE scale consisted of four scales, with the following average scores: personal development (M = 4.12, SD = 0.44), benefits to the community (M = 4.44, SD = 0.11), social responsibility (M = 4.24, SD = 0.25), and intended social responsibility (M = 4.36, SD = 1.22). All the Cronbach’s alpha for each scale is above 0.7: personal development (α = 0.89); benefits to the community (α = 0.76), social responsibility (α = 0.87), indicating reliability of the BACE scale. Intended social responsibility was assessed using a single-item measure, we did not evaluate Cronbach’s alpha for reliability.

Personal Development Scale, only three items out of ten received average scores below four (on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree): “The community engagement in this course assisted me in defining the type of work I want to do in the future,” “The community engagement in this course helped me to connect theory with practice,” and “Working in the community helped me to define my personal strengths and weaknesses”. Social Responsibility Scale, only one item, “This course helped me understand the differences (i.e., cultural, racial, economic, etc.) that exist in our community”, scored below four on average. None of the items in Benefits to the Community scored before four on average. When students were asked to rate their overall experience with the community service-learning component of the course (10 = excellent experience; 1 = poor experience), the aggregated score was 7.24 (SD = 1.29). The 10-point scale for this item was the same as used in Miller et al. (2018).

Societal Impact on the Community

Preliminary follow-up indicated that recipients, including employees, clients, and the community (see Table 7), expressed gratitude for the mask donation, and media coverage highlighted its societal impact. Throughout the philanthropic efforts, students developed essential soft skills, including coordination, communication, leadership, and civic engagement, as a result of this experiential learning activity. Several community partners continued to use the donated masks and expressed interest in future collaborations. Table 7 first demonstrated the primary functions of the five nonprofit organizations and their follow-up responses from recipients who utilized the donated masks. Although the student team agreed on the philanthropic intent, they did not directly participate in the mask donation events. Consequently, the follow-up assessment did not apply to them.

Learning Outcomes

From a student learning perspective, retailing class students engaged with multiple newspaper outlets, including those affiliated with the university. The training equipped students with career readiness (S. A. Inks & Avila, 2008) that often emphasizes the importance of oral and written communication skills. Those soft skills align with the AACSB’s learning goals. Additionally, students applied theoretical concepts from the Retail Communication Mix (Levy & Grewal, 2023), particularly in the context of public relations. For instance, students mentioned, “It demonstrated our willingness to make a positive impact within the community and showcased our commitment to help others.” (Welch, 2023) in the published news article. Another student group published their donation event on a different campus newspaper’s website, highlighting their societal impact. One student reflected, “I thought the most fulfilling part of the project was seeing how grateful veteran Lindsey Merriman was to be receiving the masks and her excitement to share them with other veterans around our area” (Burnett, 2023). Student reflections also revealed personal connections to the chosen organization. As noted in the campus newspaper interview, “Veteran Services struck an interest for each group member, seeing that we all have family members that are veterans, so we wanted to give back” (Burnett, 2023).

Students reflected in their written reports that participating in the mask donation project enhanced their understanding of the daily operations and service functions of those organizations dedicated to promoting community well-being.

Student-Run Business Establishment Framework

Based on the development process and assessment results, we propose a replicable framework for establishing student-run businesses across AACSB-accredited institutions. This Student-Run Business Establishment Framework (see Figure 3) comprises two primary components: 1) Internal Factors: Institutional support and policy alignment, technological infrastructure, student-led operations, faculty engagement, curricular integration, and mechanisms for student assessment and reflection, and 2) External Factors: Strategic partnerships with community organizations and industry stakeholders.

While each AACSB-accredited institution operates under distinct policies and procedures such as funding sources, staffing, infrastructure, licensing, and trademark regulations, the replication of student-run business models necessitates vital institutional and technological support. A diverse student body, including individuals from various academic disciplines, is more likely to engage when the value proposition of participating in a student-run enterprise is clearly communicated and demonstrated.

Faculty play a pivotal role not only in embedding the business model into the curriculum but also in mentoring and training incoming student participants. External partnerships typically emerge once the student-run business reaches operational stability. At this stage, collaborations can evolve into long-term engagements, with measurable societal impact assessed through instruments such as surveys and on-site observations.

Finally, a comprehensive assessment strategy should be implemented to evaluate both the students directly involved in the business operations and those participating through integrated coursework. This assessment should occur at the beginning and at the end of the academic term to capture developmental outcomes and learning gains.

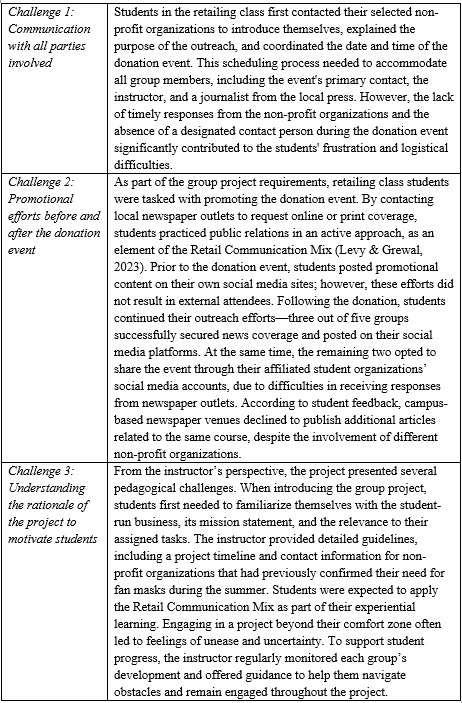

Challenges of the Retailing Course: Implementing Retail Communication Mix

The marketing activities within the retailing class focused on promoting brand awareness of the student-run business, enhancing public relations, and fostering community engagement. The mask donation event led the student team to an opportunity to present the business at a city council meeting, with the broader goal of establishing a long-term partnership with local government and community stakeholders. However, several challenges emerged while preparing for these fan mask donation events, such as logistical coordination and limited resources (see Table 8).

From the perspective of the student-run business, the initiative faces inherent issues related to continuity, particularly following the graduation of student team members. Student workers were also subject to university regulations that limited their maximum working hours. Despite these challenges, the business operates as a pass-down experiential tradition within the business school, offering students ownership of a real-world enterprise. Through this model, students engage in decision-making, marketing content creation, and strategic planning, gaining practical experience while expecting the possibility of failure as part of the learning process.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The student-run business is an ongoing process, shaped by the current stage of development and the specific areas requiring improvement. Kolb’s experiential theory

is applicable to this dynamic framework, offering a theoretical foundation for continuous learning and reflection. This study introduced an additional context by incorporating the curriculum into the retailing class and grounding the learning experience in the operation of a real business. By addressing the issue of excess inventory, students were able to apply the Retail Communication Mix within a group project while simultaneously contributing to community well-being. This integration of experiential learning not only reinforced key retailing concepts but also demonstrated the societal value of student-led initiatives.

From a pedagogical and practical perspective, this study contributed to instructional practices aligned with Kolb’s ELT. The results demonstrated that students’ participation in the community engagement activities generated measurable societal impact. Recent academic discussions aligning with AACSB standards have increasingly emphasized student-run social projects (Geringer et al., 2009; McGrath, 2023; Schwartz & Fontenot, 2007), community involvement (Cappuccitti et al., 2019; Newaz & Nilson, 2024; Schwartz & Fontenot, 2007; West, 2011), and experiential learning (Blair, 2021; Rocco & Whalen, 2016; Stutts & West, 2005). Those innovative projects have included digital community engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as virtual volunteering and online advocacy. The student-run business was initiated during this period, presenting unique challenges and opportunities. Student workers, retailing classes, and faculty were forced to innovate while maintaining safety protocols, as online instruction and global business operations continued. This context reinforced the relevance of experiential learning as a pedagogical tool adaptable to evolving educational and societal conditions.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are threefold. The first major limitation of this study was the absence of baseline data. While post-project survey data indicated positive perceptions, the lack of a pre-project survey limited the ability to attribute observed changes directly to the project. Future research should incorporate pre- and post-assessment tools to strengthen attribute changes to the project.

A second limitation involves survey design and administration. The absence of embedded attention checks may affect data reliability, particularly given the length of the BACE scale. It consists of 19 items and may induce respondent fatigue. Although the final item, a 10-point scale assessing participants’ likelihood of future community involvement, could serve as an attention check. Its effectiveness remains uncertain. The study adopted the original BACE scale structure, except for modifying the Likert scale from five to six points, a change that is subject to ongoing debate in literature (Chyung et al., 2017). Additionally, the instructor distributed a paper-and-pencil, anonymous survey at the end of the semester. To minimize missing data, the instructor reviewed each survey for completeness.

A third limitation of this study pertains to methodological constraints, specifically the reliance on the self-reported survey and a small sample size. The project was conducted within classroom settings, which inherently limits the sample size due to variations in institutional enrollment and course offerings across semesters (Bose & Ulrich, 2025; Cowley, 2025; MacDermott et al., 2023). This constraint is common in marketing education research, where studies are often exploratory, pedagogically oriented, or case-study based (Bose & Ulrich, 2025). The results generate bias and limit the robustness of the findings. These factors collectively constrain the generalizability of the results.

Furthermore, scalability remains a challenge, as the donation effort was conducted at the class level over a single semester, rather than as a sustained, institution-wide effort involving continuous donation of medical-grade supplies. This constraint was primarily due to limited institutional support.

Future Research

Future research can extend the student-run business model to diverse cultural and institutional settings, leveraging the Student-Run Business Establishment Framework (see Figure 3). Given that AACSB standards apply to accredited institutions globally (AACSB, 2023), such expansion offers a meaningful avenue for cross-contextual implementation. While the student-run business model can be adapted across cultures and AACSB-accredited schools, variations in regulatory environments may influence feasibility, especially in cross-sector partnerships. We recommend adapting validated instruments such as Civic Attitudes and Skills Questionnaire (Moely et al., 2002) or Community Service Self-Efficacy Scale (Reeb et al., 2010), which can be administered before and after events to capture changes in perceived value, community needs, and partnership effectiveness. Students could continue to benefit from the experiential learning opportunities that foster professional skills development and enhance their societal impact within the community.

Sustainable funding remains a critical challenge for student-run businesses, particularly for public institutions. In this research, operations depend on internal fundings and sales revenue. Zhang et al. (2023) suggest that fundraising and proposal communications should emphasize exploitation, the expansion of existing product lines, rather than exploration, which focuses on innovation and new product development. Promotional messaging should highlight tangible benefits such as scholarships, community reinvestment, and a sense of belonging, thereby reinforcing the value of proposition for donors and stakeholders.

In addition to cultural and regulatory considerations, future research can explore the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into advertising or branding courses (To, 2024; To et al., 2025). Grewal et al. (2024) advocate for experiential projects that incorporate AI tools such as ChatGPT and OpenAI to enhance campaign development. Cunningham (2025) analyzed the use of chatbots in luxury retail, noting their ability to deliver personalized customer service. Tools such as chatbots, digital wallets, and AI-driven interfaces aim to streamline the shopping experience. As AI becomes increasingly prevalent in generating personalized images, messages, and services, experiential learning projects may serve as practical exercises for students to implement creative advertising strategies for their clients. These innovations present promising avenues for future research into digital platform effectiveness.

In this student-run business context, student teams have repeatedly recommended integrating payment platforms such as Square or Apple Pay. However, institutional policies governing student group accounts have hindered implementation. Nim et al. (2025) examined consumer preferences in retail environments, emphasizing the importance of internet security in the adoption of cryptocurrencies and digital wallets. Given the evolving nature of consumer behavior, future research could explore the feasibility of incorporating cryptocurrency-based transactions through virtual reality or online shopping simulations. Marketing disciplines such as market research, personal selling, digital marketing, principles of marketing, and consumer behavior commonly incorporate Kolb’s ELT into their curricula.

Batat (2024) expanded the concept of phygital—a seamless integration of physical and digital experiences—into a broader framework for delivering customer value. The student-run business aligns with this framework by offering both in-person product pickup at the College of Business and shipping options to designated locations. However, the absence of a physical storefront remains a limitation. Discussions have considered establishing retail spaces within the university bookstore or other campus locations. Aligning with Batat’s framework can help identify customer pain points and improve the overall service experience.

“Reflection is a critical part of the experiential learning process” (Grewal et al., 2024), echoing Kolb’s ELT. While students may grasp marketing concepts through online instruction, applying these concepts in real-world contexts remains a challenge without hands-on experience. The mask donation project exemplifies a situational problem-solving exercise that addresses excess inventory while fostering community engagement. Future iterations could replicate this model using different products or partnerships, enabling both short-term impact and long-term learning outcomes.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

Before the actual mask donation, each non-profit organization expressed demands for the non-medical fan masks, along with plans for their intended use. Due to the simplicity of the group project and time constraint, organizations requiring small quantities of fan masks were excluded. In this case, those organizations that were not selected missed the opportunity to receive fan masks that could have contributed to the overall well-being. By recognizing the thoughtful gesture initiated by the college students, these organizations could have benefited from the donation both physically and symbolically.

In addition, the assisted living facility required background checks and consent forms for all visitors; however, since the nature of the donation did not involve direct interaction with clients, and students were not entering as visitors, the background check requirement was waived. During site visits, retailing class students aimed to minimize disruptions to daily operations, thereby preserving the privacy of clients and residents.

The donation event was coordinated at the college level through collaboration among the dean’s office, non-profit organizations, college administrators, instructors, and students to ensure compliance with legal requirements related to donations and trademark registration. Notably, only new products intended for resale require approval from the university licensing office. The fan masks had already undergone this approval process.

Conclusion

The student-run business, housed within the College of Business, provided valuable real-world experiences to its student team and offered experiential learning opportunities to retailing class students, faculty, staff, community members, and stakeholders. Guided by its mission statement, this non-profit organization aims to serve as a platform for practical learning. Although student participation requires ongoing encouragement and commitment, the student-run business offers internship and volunteer opportunities that help students cultivate soft skills applicable beyond their academic careers. Through this experience, business students gained insights into meeting AACSB standards while making a positive impact on the local community and promoting overall well-being.

.png)

.png)